One of my very first learnings all those years ago in counselling work with Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory was their tendency to talk in round-a-bout ways. At first I found this frustrating. You could not ask a direct question and get a direct answer. It will usually be silence or a head nod (which does not necessarily mean yes, but a polite acknowledgement)! So I had to find ways that clients would be comfortable to share their experience safely in ways which suited their communication style and integrated their traumatic experience. After trying the methodologies I’d learnt from narrative therapy and getting such a good response, it dawned on me that working with metaphors was common sense. Aboriginal people have been communicating in metaphorical ways since time began, through their dreaming stories and ancestors. This way of working just fits! Whether it has been in individual counselling or groupwork with women and children or in training and mentoring with Aboriginal workers, concepts or ideas are much easier to communicate through metaphorical stories, verbal or visual.

My first exposure to working with metaphors was at the Dulwich Centre. “The Tree of Life” methodology was inspired by the work of Ncazelo Ncube of REPSSI (Zimbabwe/South Africa) to respond to children affected by HIV/AIDS. I’ve used this and its sister method “The Team of Life” with children in the Tiwi Islands with great success, training local Aboriginal women to facilitate the activity. The tree metaphor gives children a safe place to stand to explore challenges and problems in their lives without re-traumatising them. I also noticed how the adults supporting the children, started talking about their own lives using trees.

“Trees can teach us a lot about how to live. Our traditional way of life is about caring for each other and growing strong families. Now there are storms destroying our families and hurting our children. We can see it’s not a healthy life for our people”. – Elaine Tiparui, Bathurst Island.

Picture: Ian Morris. This image has been used to talk about the role of the whole family/community to grow up strong kids (Grandparents are the old growth trees in the background, Uncles/Aunties and parents in middle, teenagers as younger trees and babies/toddlers the little seedlings in front).

I went on to work collaboratively with the women of Tiwi Islands and NE Arnhemland to develop a new tool using the tree metaphor to invite women into a conversation about violence and its affect on children’s development. “It Takes a Forest to raise a tree: Healing Our Children from the Storms in their Lives” is my first resource produced in community, with community, for community.

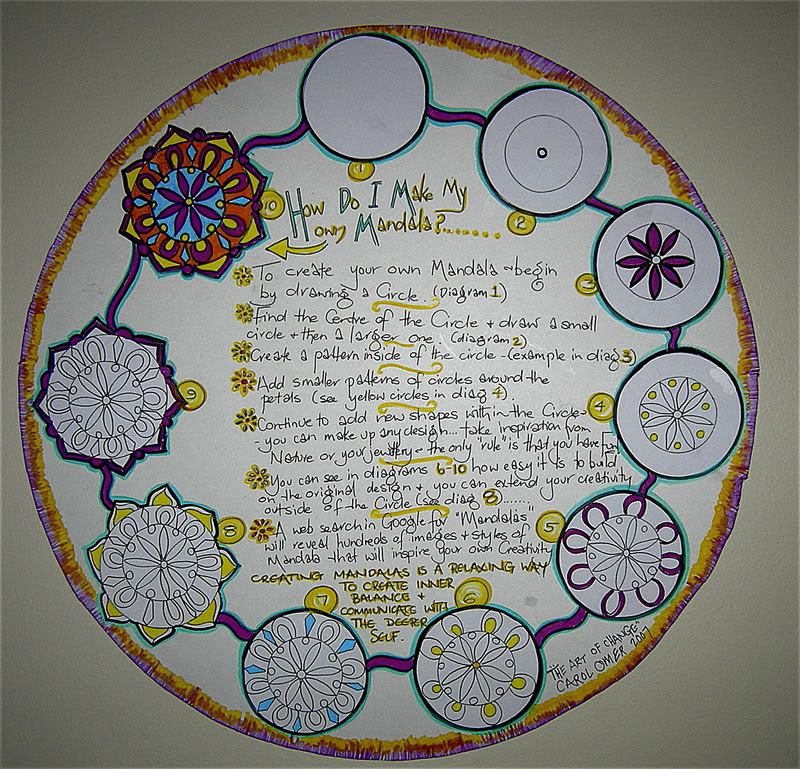

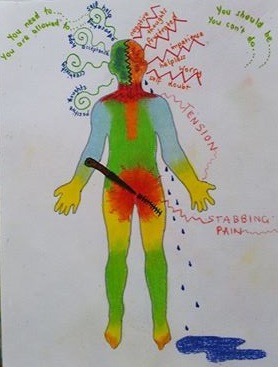

As my counselling work progressed, I found that narrative therapy still relied on people being able to verbally express a story. Neuroscience tells us that the impact of trauma on the brain means that people are simply unable to talk about what happened to them, even if they wanted to! Many of the children, I’ve worked with were still very much non-verbal and I’ve come to rely more and more on art as a method of communicating and integrating traumatic experience. Working alongside Aboriginal Child and Family Support Workers using their own languages, we discovered ways for children to document their stories of abuse, violence and neglect using methods like drawing, clay, collage and mask making. Not surprisingly these stories were communicated through aliens, imaginary friends, monsters, dreaming animals, body parts and other such creatures apart from themselves. To offer other alternative ways in to children’s stories, I also went on to write ‘The Life of Tree’, a therapeutic picture book, designed to help Aboriginal children speak up about their trauma experience. Metaphors work in the most magical way to bring healing!

…metaphorically speaking will continue to experiment with playful and effective therapeutic tools using metaphors in our direct work with clients and in the resources we produce in the future.

You can read more about how we are integrating use of metaphors with other therapeutic modalities on our page ‘How We Work’.

You can also find further resources on using metaphors in counselling and trauma work in our Professional Development Library.