In March, I was invited back to the Tiwi Islands to co-facilitate a Tree of Life Workshop with Tiwi women, as part of a ‘Telling Story’ project funded by a small Suicide Prevention grant from the NT Government.

The Tree of Life is a popular methodology that has taken off globally amongst many different kinds of practitioners working in the therapeutic space. It has very much shaped my social work practice framework and the way I incorporate use of metaphor from counselling and group work to strategic planning and evaluation.

Our workshop began with a discussion about what trees mean to the women. We heard stories about the mango trees that were planted by the old people and that sitting under the mango trees brings feelings of connection to ancestors, which keeps women strong. This connection is felt as a voice when the wind blows and the leaves start moving. “We can sense the presence, their spirit is following us wherever we go. We sense the presence of our mothers and fathers, there with us.” The mangoes are like gifts from the old people that continue to feed the children and the future generations.

Our workshop began with a discussion about what trees mean to the women. We heard stories about the mango trees that were planted by the old people and that sitting under the mango trees brings feelings of connection to ancestors, which keeps women strong. This connection is felt as a voice when the wind blows and the leaves start moving. “We can sense the presence, their spirit is following us wherever we go. We sense the presence of our mothers and fathers, there with us.” The mangoes are like gifts from the old people that continue to feed the children and the future generations.

The narrative approach is about asking questions which explore the history of the knowledge, skills and values which people describe, to thicken the story and give a richer description. As one woman described her connection to mangrove trees, we discovered she learnt to find mangrove worms to eat by going out with her grandmother and mother. She learnt how to chop that tree by observing with her eyes and listening with her ears. She discovered that the old logs were the better ones to find mangrove worms and the importance of looking for tracks first. She came to know the difference between mangrove worms and cheeky worms at an early age, by eating the wrong one. Later on in our workshop, the same woman described how the chopping action had became a way of dealing with stress in adulthood.

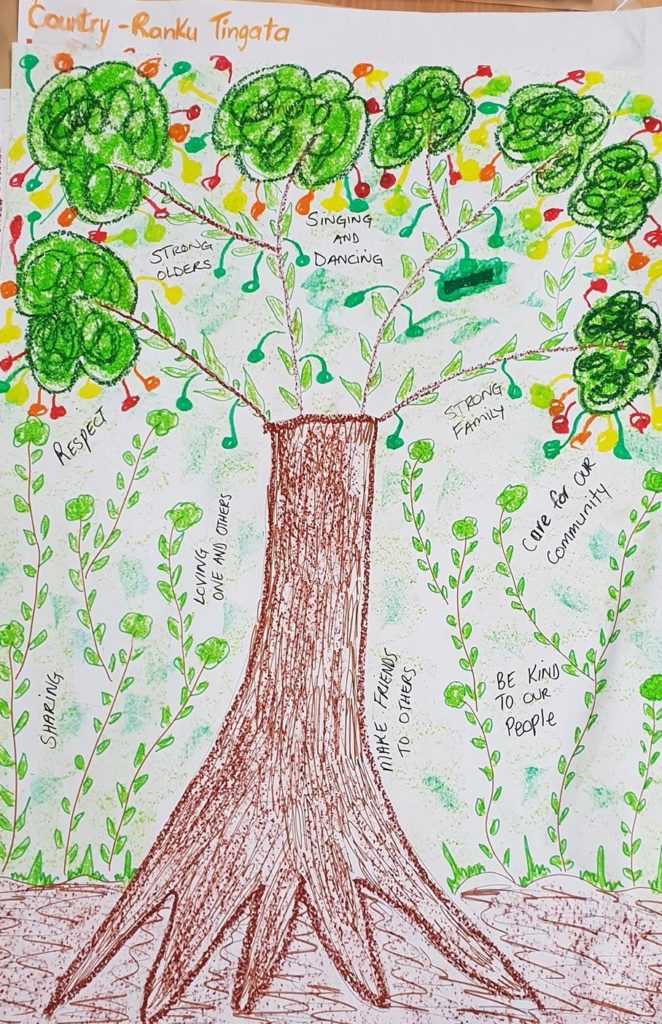

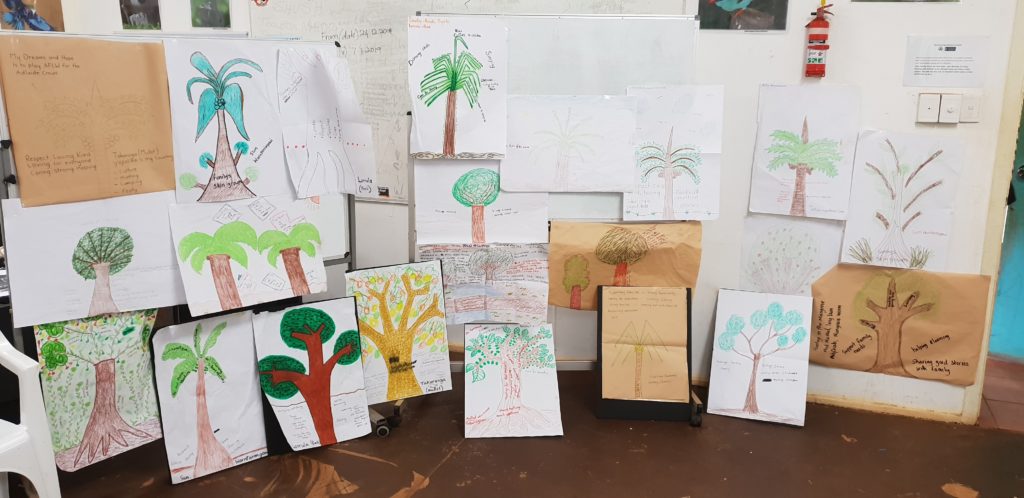

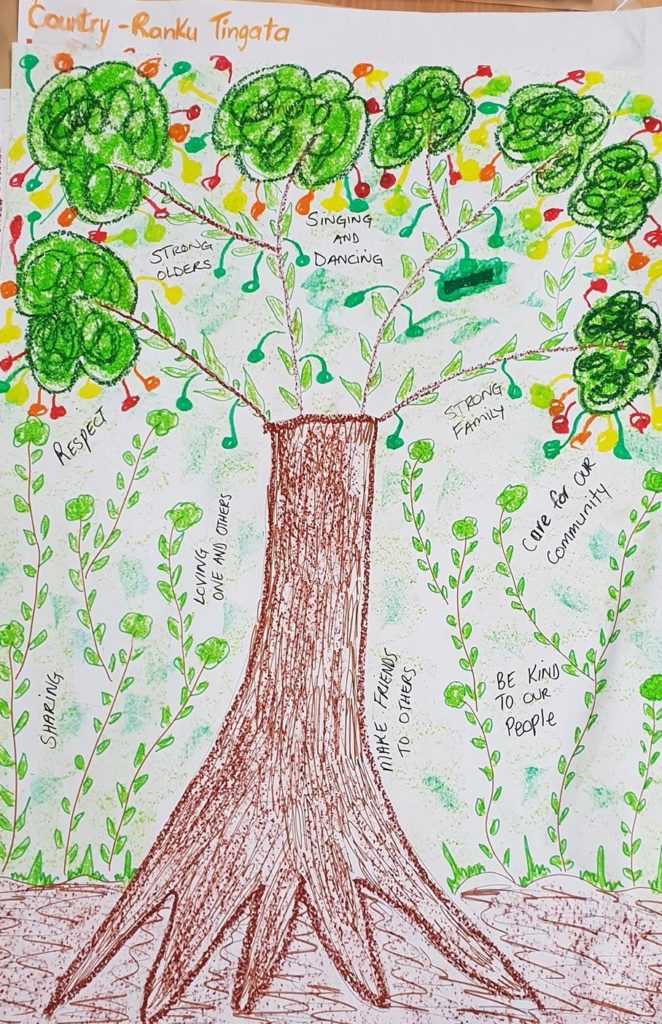

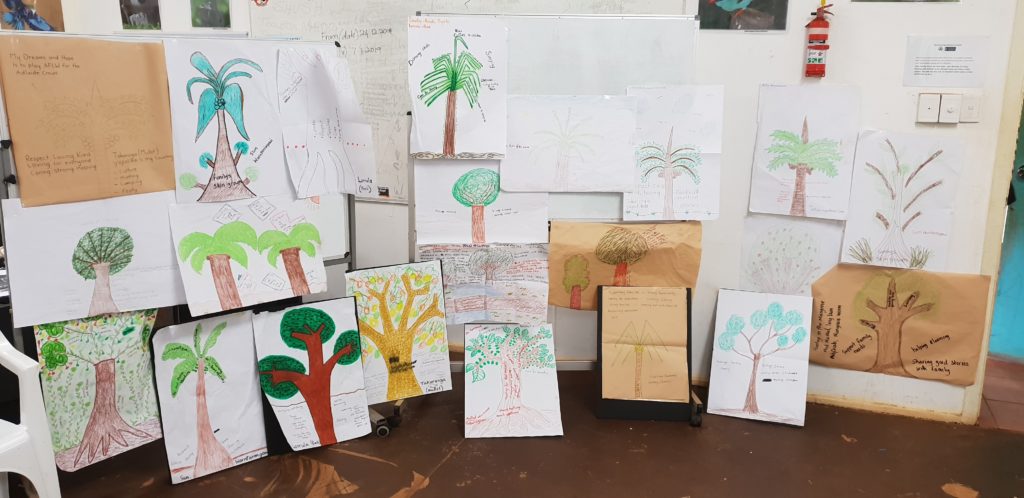

The next step of the process is inviting the participants to draw a tree, perhaps one that has meaning for them. We provided a variety of art materials such as textas, oil pastels and pencils, giving participants approximately 30 minutes to draw on an A2 size piece of good quality paper. The drawing should include roots, a truck, branches, leaves and fruit (or nuts). We then discuss the role and significance of each part of the tree and introduce the Tree of Life metaphor.

The next step of the process is inviting the participants to draw a tree, perhaps one that has meaning for them. We provided a variety of art materials such as textas, oil pastels and pencils, giving participants approximately 30 minutes to draw on an A2 size piece of good quality paper. The drawing should include roots, a truck, branches, leaves and fruit (or nuts). We then discuss the role and significance of each part of the tree and introduce the Tree of Life metaphor.

In exploring our roots which represents cultural heritage, we discovered stories of connection to country and culture, the significance of belonging to their skin groups and special places the women were connected to. These roots shaped their identities as Tiwi women. We unearthed a rich tradition of hearing “from our mothers and grandmothers, who we belong to.” For two women, there was a reclaiming of identity with the red flower skin group, which existed before the great Tiwi wars. We also heard a strong theme emerging about life-long learning, as if the roots of the trees were still growing and spreading. “Sometimes learning doesn’t stop, from little ones to big ones.” One of the women had been away from the community for a long time and had brought her children back to teach Tiwi culture. Another spoke about learning to weave much later in life. “It’s never too late to learn your culture”. The women were invited to write some words on their roots about what history stories are most important to them.

Our conversation then moved to exploring the trunk of the tree representing people’s skills, abilities and values. We noticed that some women found it difficult voicing these qualities, so we asked what important people in their lives might notice or appreciate about them in order to uncover hidden stories. We heard stories about making art, collecting dyes for basket weaving, keeping children safe and looking after them, getting children to school every day, being a bridge between Tiwi and non-Indigenous people coming to the islands, and being the best damper maker in the family. Many women inherited the skills of teaching and were committed to sharing their knowledge with the next generation. Shared values of women supporting each other and keeping culture alive through dance, song and story were named, and how this contributes to their ‘trees’ staying strong. Once again, the women documented which stories were significant to them on their tree drawing.

In exploring wishes and dreams for the future (or the strong branches reaching out), we heard shared dreams about changes for their community. We heard hopes for Wurrumiyanga to be a better place to live, a safe place to live with no violence. One woman dreamed about people in the community changing their attitudes, so that there is more respect, love and kindness. She modelled this in her family through soft, gentle talk, not growling. Others said they wanted young people to sit and learn from the Strong Elders, for kids to grow up and have a better life, to see them learn the skills of singing and dancing. One woman wanted to talk stronger with kids when they are fighting, because she didn’t like seeing kids hurt each other, and then adults getting involved in the fighting. There were grand hopes for a cultural centre to be built to preserve Tiwi culture, and smaller hopes for teaching basket weaving and armband making. These wishes were linked to deeply held values of passing on strong culture to their children, so they can grow up to be the next generation of strong leaders.

Each of the women then shared personal hopes and dreams for their lives. This included being a model, a teacher, a teachers assistant, hunters and fishers, supporters and helpers and being a better person. Women’s hopes and dreams were recorded with photos, a moment captured in time to bring to life.

“I want to be a singer. Nana has been teaching me singing since I was about 15 years old. I want to teach kids how to sing when they grow up. They will teach their kids in the future.”

“I want to be a singer. Nana has been teaching me singing since I was about 15 years old. I want to teach kids how to sing when they grow up. They will teach their kids in the future.”

“I’d like to play footy for a women’s AFL team, hopefully the Adelaide Crows. I’ve had this dream since I was a teenager. My grandfather saw my talent. He’s passed away now. But he would say “Play footy and be a good sportswoman, and be a part of it”. I carry his voice with me.”\

Over 30 women attended the two day workshop. This was a greater number of participants than expected, and posed a challenge for us, as facilitators, ensuring all voices are given an opportunity to be heard. It also meant that time didn’t allow us to investigate the leaves (special people) and fruits (their gifts) as fully as we would have liked. However, as you can see from the above quotes, this tended to occur naturally in our investigation of people’s stories. The importance of knowing their roots, the history of their skills and abilities, and their hopes and dreams for the future, often uncovered people who were important to them and the legacies they had left.

In Day two of our workshop, we explored what it is like to be part of a Forest of Life. The women voiced “We are all one family – we are all Tiwi” as well as recognised the unique stories and skingroups, values and beliefs, skills and abilities, hopes and dreams of each tree. Standing back to visualise the forest of trees revealed the beauty that came from standing tall and proud, healthy and strong. This was seen as a place where the women support each other, look out for each other, offer care, kindness, and protection.

In Day two of our workshop, we explored what it is like to be part of a Forest of Life. The women voiced “We are all one family – we are all Tiwi” as well as recognised the unique stories and skingroups, values and beliefs, skills and abilities, hopes and dreams of each tree. Standing back to visualise the forest of trees revealed the beauty that came from standing tall and proud, healthy and strong. This was seen as a place where the women support each other, look out for each other, offer care, kindness, and protection.

Our final discussion around the Storms of Life unveiled the kinds of storms that women come up against. This included domestic violence, fighting, arguing, jealousing, hate, family violence, gossip, swearing, hurt feelings, speaking bad way- especially on facebook, ignoring people, lateral violence, discriminating, putdowns, tantrums and losing family. We explored the skills, strategies and knowledge women draw upon to stand strong in the face of these difficulties. This knowledge was recorded in a document called ‘Weathering the Storms of Life’. It is hoped that this document would help the women ride out future storms that might blow their way.

In the concluding moments of our workshop, the women spontaneously expressed a wish to send a message to their children about their hard won knowledge and skills regarding managing storms. This is their message – Words for Our Children.

The women of Wurrimyanga, Tiwi Islands

Sometimes, the most powerful process to occur happens after the group work is finished, by inviting other communities or individuals to witness and respond to the stories that have been gathered. Contributions from these ‘Outsider Witnesses’ can help the storytellers feel connected to others, reduce isolation, and assist them to take action in line with their intentions and commitments. Having a group of outsiders listening and acknowledging people’s wisdom and knowledge, validates their story and identity claim (Carey & Russell). The Telling Story Project team will be taking Tiwi messages back to other communities they work in, to exchange messages.

If you would like to be an Outsider Witness to the stories of the Tiwi women, I invite you to download and read ‘Weathering the Storms of Life’. Use the four questions below to formulate your message and send it to us. We will make sure your message gets sent back to the Tiwi women.

- Which words in this document capture your attention?

- What do you think these words suggest about what this person values, values, believes in, dreams about or is committed to?

- Is there something about your own life that helps you connect with these words? Can you share a story from your own experience that shows why their words meant something to you.

- So what does it mean for you now, having read this document? What might be different in your life?

We look forward to hearing your story.

This video presentation offers a visual snapshot of our 2 day workshop.

If you would like to know more about using the Tree of Life methodology in your community, please contact us or Sudha Coutinho at the Telling Story project on sudhacoutinho@gmail.com. We would be happy to work with you in capturing the wisdom and knowledge of your community or group, in riding out the Storms of Life.

This Telling Story project was funded through a NT Government Department of Health Alcohol Reform NGO Grant and auspiced by Relationships Australia, NT.

References and further reading:

Denborough, D. (2008), ‘The Tree of Life: Responding to vulnerable Children’ in ‘Collective Narrative Practice: Responding to individuals, groups and communities who have experienced trauma’, Dulwich Centre Publications.

Carey, M. & Russell, S., (2003) ‘Outsider-witness practices: some answers to commonly asked questions’.

Our workshop began with a discussion about what trees mean to the women. We heard stories about the mango trees that were planted by the old people and that sitting under the mango trees brings feelings of connection to ancestors, which keeps women strong. This connection is felt as a voice when the wind blows and the leaves start moving. “We can sense the presence, their spirit is following us wherever we go. We sense the presence of our mothers and fathers, there with us.” The mangoes are like gifts from the old people that continue to feed the children and the future generations.

Our workshop began with a discussion about what trees mean to the women. We heard stories about the mango trees that were planted by the old people and that sitting under the mango trees brings feelings of connection to ancestors, which keeps women strong. This connection is felt as a voice when the wind blows and the leaves start moving. “We can sense the presence, their spirit is following us wherever we go. We sense the presence of our mothers and fathers, there with us.” The mangoes are like gifts from the old people that continue to feed the children and the future generations. The next step of the process is inviting the participants to draw a tree, perhaps one that has meaning for them. We provided a variety of art materials such as textas, oil pastels and pencils, giving participants approximately 30 minutes to draw on an A2 size piece of good quality paper. The drawing should include roots, a truck, branches, leaves and fruit (or nuts). We then discuss the role and significance of each part of the tree and introduce the Tree of Life metaphor.

The next step of the process is inviting the participants to draw a tree, perhaps one that has meaning for them. We provided a variety of art materials such as textas, oil pastels and pencils, giving participants approximately 30 minutes to draw on an A2 size piece of good quality paper. The drawing should include roots, a truck, branches, leaves and fruit (or nuts). We then discuss the role and significance of each part of the tree and introduce the Tree of Life metaphor. “I want to be a singer. Nana has been teaching me singing since I was about 15 years old. I want to teach kids how to sing when they grow up. They will teach their kids in the future.”

“I want to be a singer. Nana has been teaching me singing since I was about 15 years old. I want to teach kids how to sing when they grow up. They will teach their kids in the future.” In Day two of our workshop, we explored what it is like to be part of a Forest of Life. The women voiced “We are all one family – we are all Tiwi” as well as recognised the unique stories and skingroups, values and beliefs, skills and abilities, hopes and dreams of each tree. Standing back to visualise the forest of trees revealed the beauty that came from standing tall and proud, healthy and strong. This was seen as a place where the women support each other, look out for each other, offer care, kindness, and protection.

In Day two of our workshop, we explored what it is like to be part of a Forest of Life. The women voiced “We are all one family – we are all Tiwi” as well as recognised the unique stories and skingroups, values and beliefs, skills and abilities, hopes and dreams of each tree. Standing back to visualise the forest of trees revealed the beauty that came from standing tall and proud, healthy and strong. This was seen as a place where the women support each other, look out for each other, offer care, kindness, and protection.

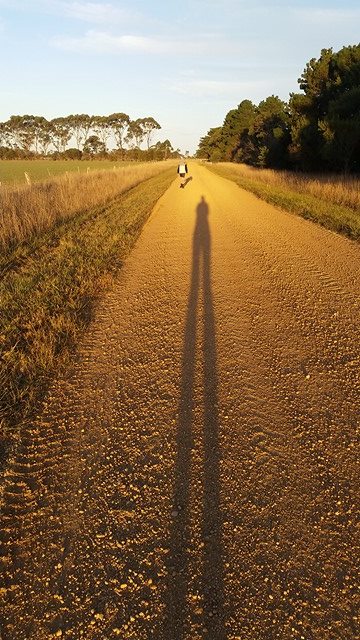

I watched him as he sat at a safe distance plucking up the courage to look back at the strange phenomenon he had just encountered. It must have been a shocking discovery to find me sitting there. I couldn’t help but feel sad that he wasn’t brave enough to continue on past me, as if I was invisible. Or just a part of nature too. Part of his web of life.

I watched him as he sat at a safe distance plucking up the courage to look back at the strange phenomenon he had just encountered. It must have been a shocking discovery to find me sitting there. I couldn’t help but feel sad that he wasn’t brave enough to continue on past me, as if I was invisible. Or just a part of nature too. Part of his web of life.