I received an invitation from a colleague this year to travel back to the Northern Territory to co-facilitate some narrative therapy group work with the Aboriginal women of Borroloola. We had it all planned out. It would have been a two day drive from Darwin to reach the remote township, then a trek over to Barrnayi, an island off the coast of the Gulf of Carpenteria for our two day camp. I love it when collaborations like this come together – Telling Story, Artback NT and the Moriarty Foundation – bringing together good will and established therapeutic practice for positive community outcomes. What we didn’t account for was the arrival of COVID 19 and the immediate closure of state and territory borders as well and lockdown in remote communities.

Airfares were cancelled. However, I wasn’t about to shelve this one without some serious thought into whether delivering the Tree of Life on-line was a possibility. I learned later that this is called pivoting!

I had some doubts about whether we were going to be able to gather rich story from participants over a technology platform. However, Sudha Coutinho had done a lot of work in Borroloola and already had established relationships with some of the women, so that was a positive starting point. With some thoughtful deliberations and program modifications to the Tree of Life methodology, Sudha and I decided to ‘set sail’ and see where the adventure might take us on these unchartered waters.

We were very influenced by the beautiful work done by Anne Mead and Jasmine Mack in their application of the Tree of Life with parents of Roebourne. Ideas such as home yarning, the tree visualisation meditation and crafting a community tree appealed to us. Given the extra difficulties we would face interacting over a screen with our participants, we needed to pay attention to ways people could join in that did not require so much hands-on guidance.

The program was delivered over five weekly morning sessions consisting of three hours with a break in the middle. We posted out a big box of materials required including art supplies and resources prior to starting. We hoped that our local Yanyawa Project Officer could work alongside us in navigating the use of these materials. Each session generally consisted of an introductory activity such as using Tree Card images we created to check in with how people were feeling, followed by a yarning section with corresponding drawing or art making, and a collective conversation on what these stories meant to the community as a whole, then finishing with an invitation to undertake an exercise at home between sessions. We invited people to connect on the Workplace Chat App on their mobiles to continue the conversation and share images of what they discovered in their environment between sessions. This is also where we, as facilitators, shared therapeutic documents based on the ‘rescued words’ from each session. These five therapeutic documents were later incorporated into a Tree of Life booklet the women wanted to publish capturing their skills, knowledges and hopes for raising strong and healthy children.

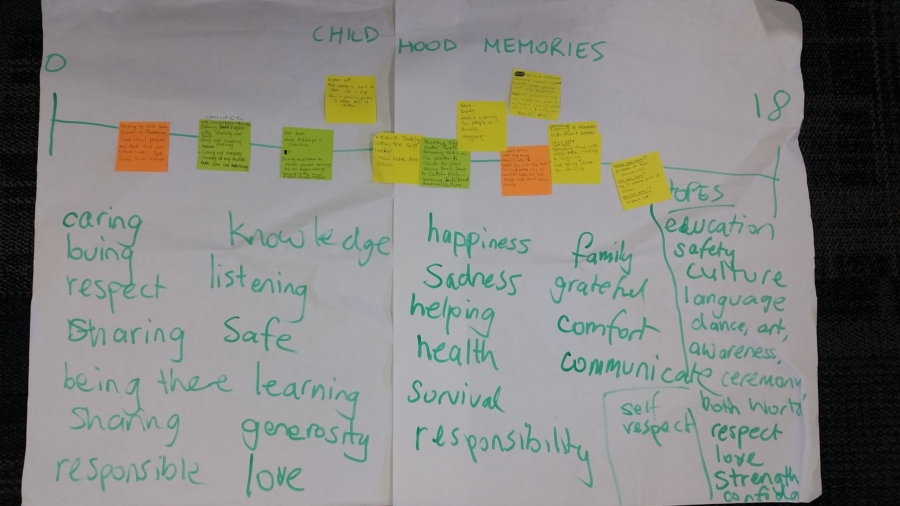

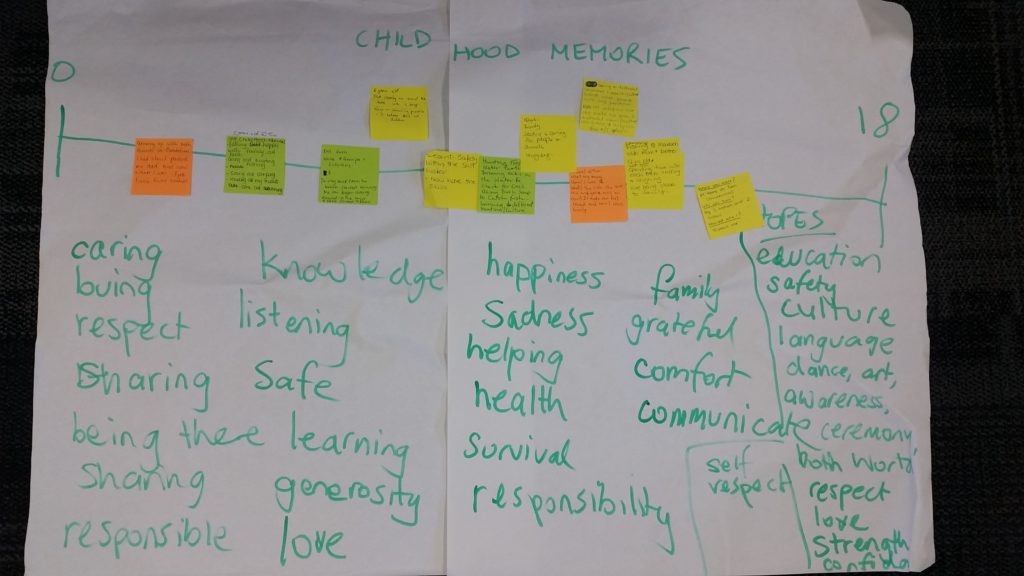

Over the project the following themes were explored using the tree as a metaphor for growing up strong children in the community.

- The Sun – principles of caring. Just like the sun shining down on little trees guides their growth, the principles that are important to us guide our caring.

- Roots – History of place and story. The roots follow the history of culture, linking us to stories, traditions and places of significance.

- Trunk – Strengths of skills and knowledge. This includes the practical things we do to keep our families strong and to hold up our kids.

- Bark – The Protective Layer. Acknowledging the need to protect our children because the types of experiences our children have in life influence their development.

- Leaves and Fruit – The important people and their gifts to us and our children.

- Storms of Life – The things that try to get in the way of us bringing up strong and healthy kids and how we stand strong against them.

- Branches – Our hopes and dreams for our children and family.

- Planting Seeds – The actions we want

to take to make our hopes and dreams grow.

and; - Flowers – Ways we want to work together to make our community dreams blossom.

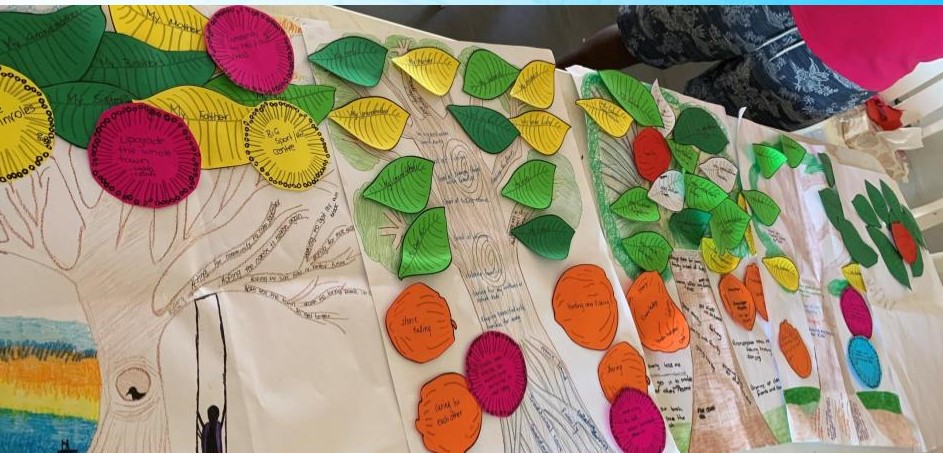

The women brought together their completed individual tree pictures and shared together their hopes for the future of their community as a ‘Collective Forest’ to stand strong against the storms of life. We finished on physical actions of planting seeds into flowerpots as a reminder of their hopes and dreams coming to life, slowly but surely.

We had to make lots of changes on the go and this required some quick thinking and flexibility on our part. We needed to feel not so precious about sticking to our script, even more so, given the lack of ability to just jump in physically and rescue a situation. The struggles as well as the delightful outcomes of this work are explored extensively on the video below, so I won’t repeat those here. Let me just say that our doubts about gathering rich story were well and truly blown out of the water. We gathered so much beautiful knowledge and wisdom from the mothers, aunties and grandmothers that participated, we couldn’t fit it all in the booklet. If you do not have access to a hard copy, you can read an on-line version here.

The following video is a 17 minute snapshot of this work presented at the AASW 2020 Symposium. Meanwhile, If you’d like to know more about using the Tree of Life over ‘Zoom’ technology, please contact us. We are really open to sharing our work with you.

Invitation to be an Outsider Witness to the women’s stories from Borroloola

Reading the Tree of Life booklet about raising strong and healthy kids in Borroloola may spark thoughts about your own skills and knowledge, your hopes and dreams for your children, and help you stand against any storms you may face. If you would like to share these thoughts with the women you can email Telling Story at sudhacoutinho@gmail.com

While some research findings have limitations, here are some of the trends worth noting.

While some research findings have limitations, here are some of the trends worth noting.