Caught in a wet season storm at Yirrkala Women’s Centre.

I have the most beautiful memories of my work out at NE Arnhemland. I was amazed by how much I achieved in such a short time, given that I did not have relationships in the communities of Nhulunbuy or Yirrkala. The most special part was finding Nami White who I ended up employing to work with me in the Children’s Counselling program. In 2010 she invited me to go to her outstation at Buymarr for three days. I used the time out bush to document how Nami and I were operating in the space where two worldviews meet and I recently stumbled upon my writings. At the time I really appreciated being able to reflect on my social work practice in this way. I hope it inspires you to do the same.

A MODEL OF PRACTICE: WORKING TOGETHER FOR HEALING

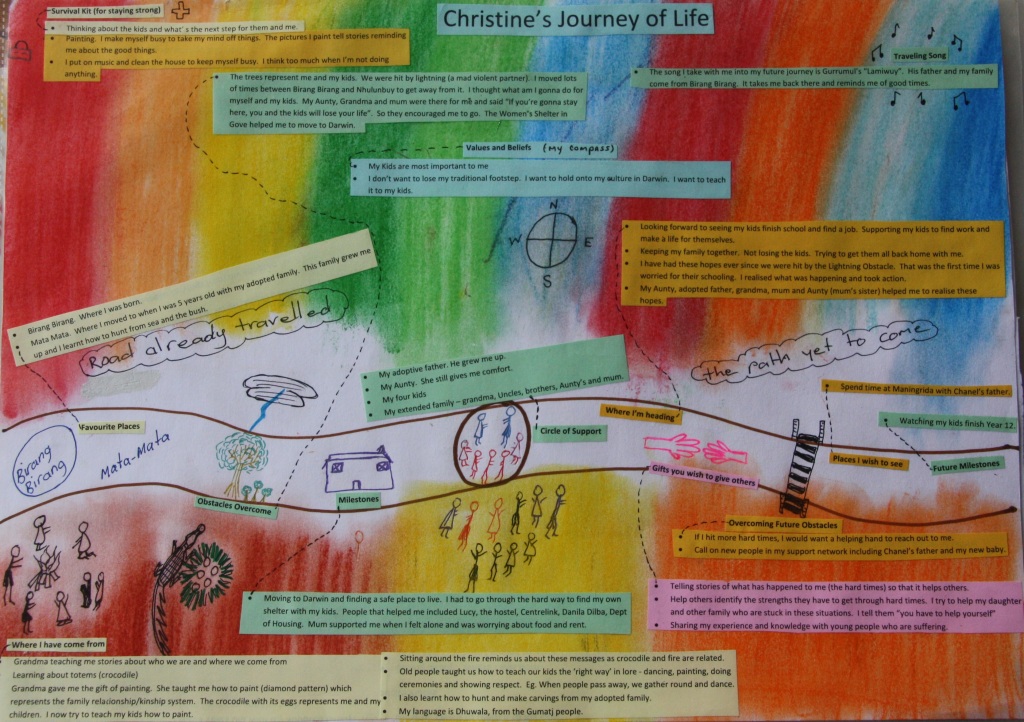

This document brings together ideas from Nami White and Lucy Van Sambeek who work under the SAAP Children’s Project for Relationships Australia. It aims to show how Yolngu and Western worldviews are working together to bring healing to the lives of children, their mothers and families affected by domestic and family violence.

This document was created from a conversation which occurred while camping at Buymarr, an outstation where Nami often visits and stays with family when she needs some time away from her community of Yirrkala. On this trip, Nami brought her grandson to provide him with an opportunity for counselling and traditional healing to address some of the difficulties he is experiencing in his life.

This process has given us new insight into each other’s world view and an appreciation for what we each bring to the work, what we are doing and how we are doing it. Perhaps these ideas might be of use one day to other workers who are trying to marry Western approaches to counselling with Yolngu methods of healing.

Knowledge

Together we bring a wide variety of knowledge to the work, derived from formal education, life experience, observation and history. We have a shared understanding about the nature of domestic and family violence. Lucy says that:

- Men are more likely to be perpetrators of violence than women

- Children are the silent sufferers

- Drugs and alcohol affect people’s behaviour but is not a cause of violence. We know this because not all drunks are violent

- Children are affected by being a witnesses to violence

- Sometimes it is difficult to see the effects of violence in children. The quiet child is not necessarily seen as a child of concern.

- Parents may not recognise the effects violence has on their children

- Trauma from domestic violence can have life long effects

Nami connects with children in the community through art and storytelling.

Nami brings knowledge about domestic violence and family violence watching children and parents in her own community and family. She worked for many years in the voluntary-based women’s night patrol, walking on foot around the community looking out for children. Nami can recognise those children that are quiet and frightened, “don’t want to mix with other children”, and “can’t be who they want to be”. Some children want to be with others but are prevented from doing so by adults who act protectively to keep them away from other children, for fear of getting into a fight. Children take a long time to talk up about their situation with someone they trust – this could be out of fear or shame. They may not want to get into trouble.

Children can take sides with their mother or father depending on what they have been led to believe by the perpetrator. When violence is happening children react different ways, some may try to protect their mother, try to stop the fight and disarm weapons while others may run or hide.

Shame can prevent women from speaking up about domestic violence. Shame can stop men from admitting fault or taking responsibility for their behaviour. Women are likely to stay in a relationship which is violent as leaving the relationship could bring shame to her and the family. However, if the fear is strong enough women have been known to leave their partners, children and community as they feel they have no choice. They are often seen as the ones to blame.

The Western world would say that formal theories shape our understanding of observations such as these. This includes knowledge about family systems, social learning, behaviour, a holistic view of health, the cycle of violence and trauma responses. Nami also brings knowledge gained from her experiencing of living with a violent and jealous husband. She also knows what it is like to live in a gentle and loving relationship. Living with violence has given her insight into what causes violence, what it feels like to live with violence and what signs to look out for in other women. Nami has seen men become physically sick from perpetrating violence, as a result of the bottling up of guilt and shame. Serious sickness can become a precursor for a change of behaviour in the perpetrator.

Nami has also had two fathers as positive role models who have taught her to be on the look-out for warning signs. Her fathers used to tell Nami stories about times they intervened in family disputes often putting themselves in the face of danger. Their message to her was to practice the same ways, stand up strong to help Yolngu people and live by the lore. With the support of her father, Nami once confronted a hostile man saying “I’m not afraid if you hit me or hurt me”. He taught Nami how to love the enemy. This old man was a respected Elder who knew how to operate in the world of Balanda and Yolngu.

As a girl, Nami also learned about how to live a good life and how to treat other people through women’s ceremonies. We also bring knowledge about recent histories events in Nhulunbuy and surrounding Aboriginal communities, and how these have impacted on the spirit and behaviour of Yolngu people. Nami says the introduction of alcohol has had devastating effects, creating divisions within families, and between the generations, through the perpetration of violence. Elders are sick and tired of the violence caused by alcohol in their communities.

With the introduction of mining in the area, came a system of royalties paid to traditional owners of the land and their families. However, Nami sees that the system is not equal and fair, with the most powerful and greedy landowners, handing out the money as they see fit. The impact of this, filters down to families where disputes over royalty handouts not paid, erupt into bouts of drinking and violence. Traditional values about caring for the land have been replaced with concerns about power and money.

Values and Beliefs

Social justice and human rights are foundational social work values that underpin our work with children and families. Lucy says this is pertinent when working with Aboriginal communities, who continue to suffer from the effects of discriminatory policies and practices from governments. Finding ways of working which reclaim the dignity, respect and self-determination of individuals, families and communities is of utmost importance.

Together we believe:

- All people including children have a right to feel safe

- All people have a right to be treated fairly and with respect

- All people should have an opportunity to make decisions that affect their own lives

- Violence against any person, particularly woman and children is unacceptable

- That there is always hope and therefore change is possible.

Nami believes that role modelling her values and beliefs through her behaviour can show people alternative ways of living and being to violence. For Nami this means being gentle, kind and caring, sharing with others; treating others how she wants to be treated; showing respect, and following lore and cultural beliefs. These values have developed over a lifetime but were significantly shaped at the death of her son during alcohol-fuelled violence. Rather than take revenge against the other family, Nami chose to act with forgiveness and found a non-violent path through prayer. Her commitment to Christian values, gives Nami the strength to “love the enemy”. Nami’s father was also a significant role model who had “love for everyone”. Although her heart has been broken many times, Nami knows that she is a stronger woman today for surviving difficult times in her life. Her drive to help her own people by living out her values is significantly shaped by her life experience.

Skills

Nami reads a book about fighting to the children during a group session on the beach.

It may seem like a basic counselling skill, but attentive listening is so important in this work. Aboriginal people have been ignored for so long, that it would be unjust and disrespectful to continue to impose Western solutions to Aboriginal problems without listening to their own expressed needs, hopes and dreams for change. Lucy’s strengths are also in asking the right questions in ways which are appropriate for Aboriginal communication styles, developing trust and rapport by focusing on building relationships, finding creative and safe ways for people to tell their stories, identifying people’s strengths and supports, linking people in to other services or workers, and having genuine positive regard for people with an open mind and non-judgemental attitude.

Nami feels that she is often at the forefront of family and community disputes as a mediator. Her skills are in using her “voice” in “strong hard ways” so that people get the message that violence won’t be tolerated. She reminds people fighting of their kinship ties and the responsibility this brings. She also knows when it’s the right time to walk away, in order to prevent getting caught up in violence acts herself.

In our counselling work, Nami is instrumental in gaining the trust of children and putting adults at ease, by communicating in her first language about our roles and the work we do. She is a translator and cultural guide for Lucy. Nami knows when it is the right time to talk about difficult issues with children and when it would be inappropriate, by reading intuit body language that looks quite unremarkable to Lucy. Nami’s intuition tells her when a child could become upset, angry or re-traumatised. Such information is vital for the counsellor.