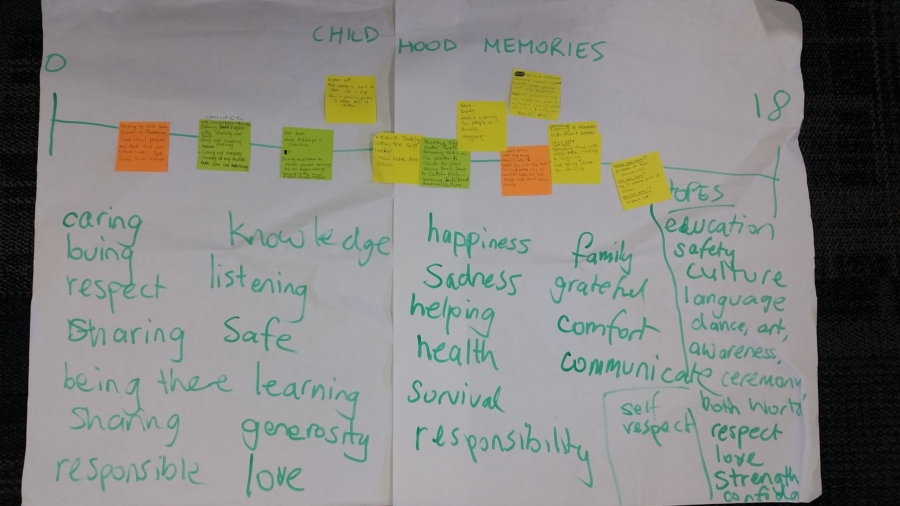

Bloopers captured in time on our crowdfunding campaign video

This blog goes out on the cusp of the release of my first children’s therapeutic picture book. Nerves aside, it’s been an exciting but hectic week as Christine and I prepare for media interviews. We’ve also been busy creating a crowdfunding campaign to get the community on board with our hopes for the book. We are new to all this stuff, so of course there have been many laughs along the way (hence the blooper snapshot captured here while filming our campaign video). If you really want to know what all the fuss is about, then maybe this Q&A might provide some answers.

What is the book about?

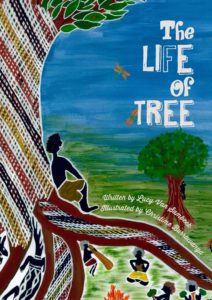

There are two characters in the book, a little boy called Jack and his friend Tree, who lives with his family (or other trees) in the bush. I think the blurb on the back cover is a good summary of what happens in this story.

“Tree is living a peaceful life in the bush until a wild storm comes along and damages his environment. His friend, Jack is worried that Tree won’t recover and be able to play with him again. When Jack also lives through a wild storm in his home, he comes to realise just how strong they both really are. Jack has strong cultural roots, just like Tree that brings hope and healing to his whole family.”

This story is really exploring the ‘storms of life’ that children go through and how this impacts on them. It’s also a story of healing which comes through connection, culture and the support of family and community.

How did this story come to me?

The story was just slowing coming together in the back of my mind, mulling away there for a long time. Then one day, I think I was in a day dream state and the idea just popped into my head. I then went away and wrote it fairly quickly. Often ideas come to me in my dreams day or night.

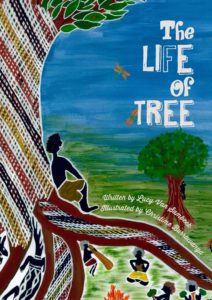

Book Cover

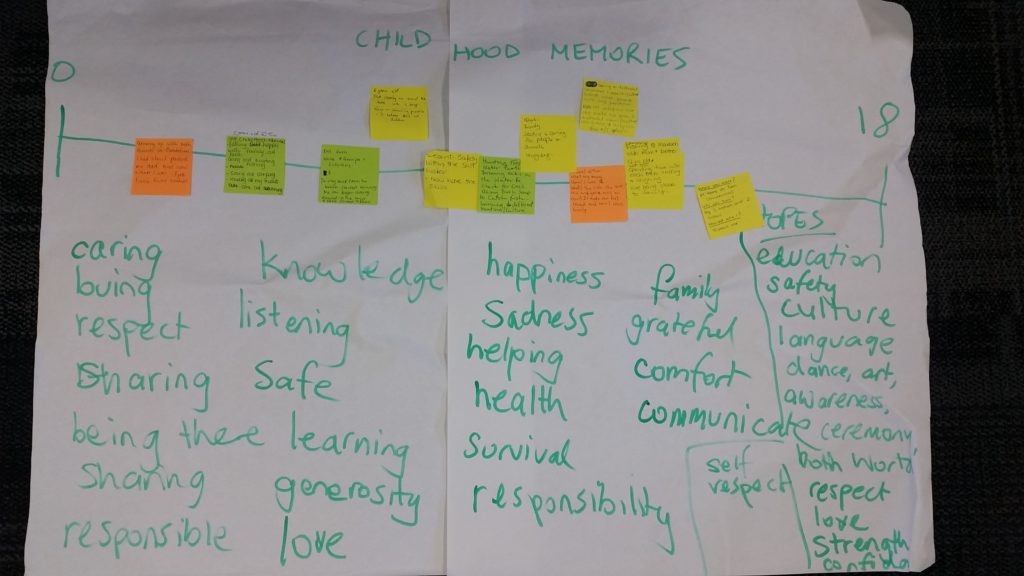

What are the aims of the book? What are my intentions in writing it?

I think the book reflects what I am trying to do in my counselling work with children. First, it’s about helping them find their voice and give words to the ‘problem story’ of their lives. It’s also about making visible the ‘strong story’ of their lives – what is it that is keeping them going, stay safe and be happy.

I am hoping that the adults in children’s lives will use this book to give voice to the strong story of children’s lives and perhaps even document this. This could include the skills, abilities, beliefs, values and knowledge the child has in coping and keeping themselves safe.

‘The Life of Tree’ is another resource that people can add to their tool box in their conversations with children.

Who is the book for? Who would be interested in reading it?

This book is intended to be read by an adult to Aboriginal children who have been affected by trauma.

This book will appeal to Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people care for, live or work with children who’ve experienced trauma such as domestic and family violence. So this can include family members and foster carers as well as professionals such as counsellors, social workers, support workers or case workers.

What inspired me to write the book?

My biggest motivation is to help children tell their stories. One of the greatest challenges I’ve faced in my work with Aboriginal children, apart from the obvious cultural and gender barriers is gaining enough trust, for children to feel that it is OK to talk about the really tough stuff. And that what they are feeling is normal. Kids do feel sad and angry about violence in their families. And it’s shame and fear that really hold them back from speaking up and healing from their experience. So in order to gain trust we need to create a safe space for the conversation.

Another motivation is to provide a culturally safe tool for professionals. ‘The Life of Tree’ uses images and themes that children can connect to because it reflects their own cultural traditions and beliefs. Christine has done an amazing job bringing her artistic talents to this story. I haven’t really found any other resources like this out there.

Of course, my favourite part is the use of metaphors because this has worked in other areas of my practice. I’ve been practicing narrative therapy in my work with children for 8 years, with groups of children in remote communities as well as in individual counselling. I have witnessed how the use of metaphors is effective in connecting with people and creating a safe space for conversation about difficulties in their lives. Asking direct questions isn’t always going to work, but people seem to spontaneously want to share their own story, if they hear a story that is similar to theirs.

What initially got me interested in this topic?

10 years ago I arrived in the Northern Territory virtually green from university. The first 6 months working out bush as a drug and alcohol counsellor, I drank lots of tea and did a lot of listening. I later moved into children’s counselling and I was hearing lots of stories from women Elders about their concerns for their children and grandchildren. I guess, I’ve always been listening for ways I might be able to meet an expressed need – that’s what community development is all about. If there is some way I can walk alongside communities to find solutions to the problems in their communities, then there is a place for me there. Along the journey I’ve found myself more and more in the healing space, finding ways of bring healing to people’s lives.

When is the book being released? How can people buy it?

The book was released on Wednesday 1st March 2017. You can access further information and a Sneak Peak of pages from the book from my online Shop. There you’ll also find a downloadable Order Form.

What about people who can’t afford to buy the book?

We are officially launching a crowd-funding campaign on Tuesday to raise money to send free books to communities. Christine and I would like to put donated books into all the women’s refuges in remote communities of the NT, WA and Queensland. We are both aware that the support for children coming into remote safe houses is pretty limited. ‘The Life of Tree’ is one way, that Aboriginal workers in those services could engage children and directly support them.

So if there is anyone out there who would like to sponsor a book, they can look up our campaign ‘Giving Aboriginal Kids a Voice’

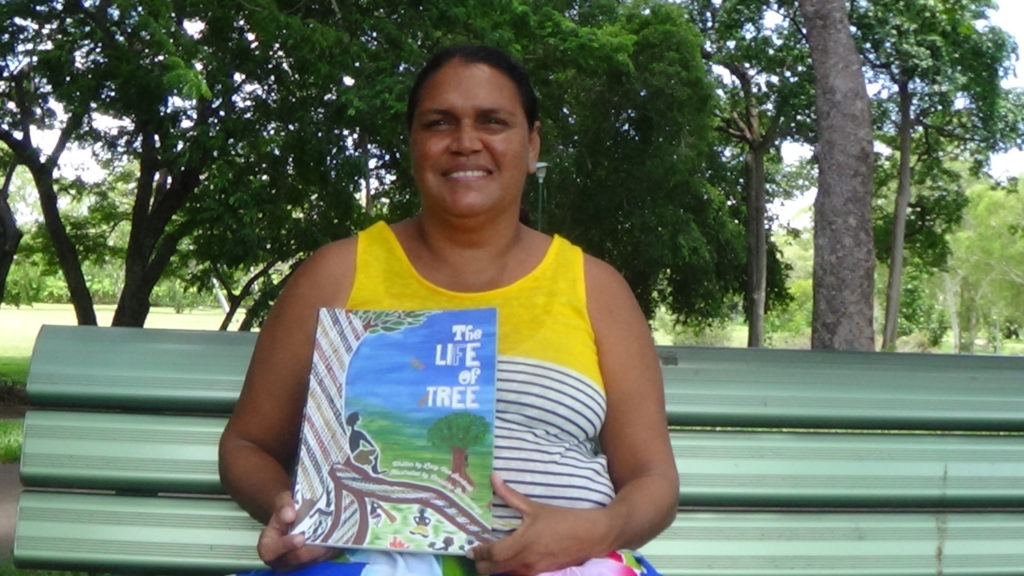

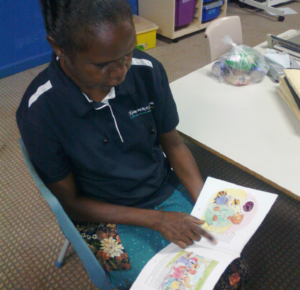

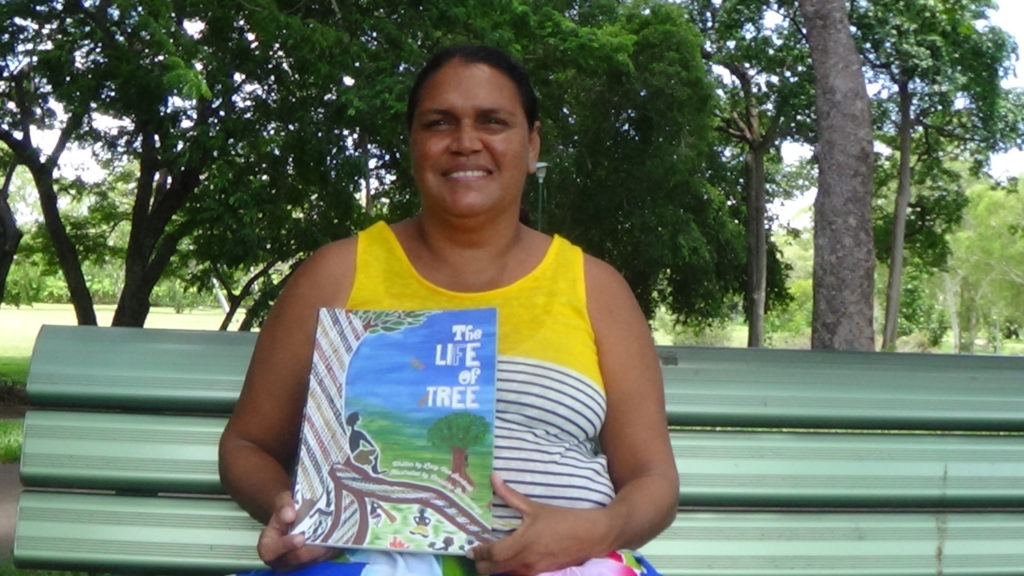

Christine with ‘The Life Of Tree’