The strong pull towards evidence-based practice demanded by funding bodies creates dilemmas for social workers who also have a commitment to community development, empowerment and anti-oppressive practices. So how does one undertake a project evaluation in a remote Indigenous community if trying to marry Western evaluation processes with cultural safety? My current project working with a Review Team consisting of local Aboriginal community members may offer some food for thought.

In our first meeting together, we spent quite a lot of time exploring what evaluation is, so that everyone had a grasp of what it was we were trying to achieve. During this process, I found myself observing our independent external evaluator using language that was just too difficult to understand. A lot of big words. Too many words. Inputs, outputs, outcomes and impacts. Quality criteria, KPI’s and program logic. It was making my mind boggle, let alone those whose minds are converting English to Tiwi language and back again.

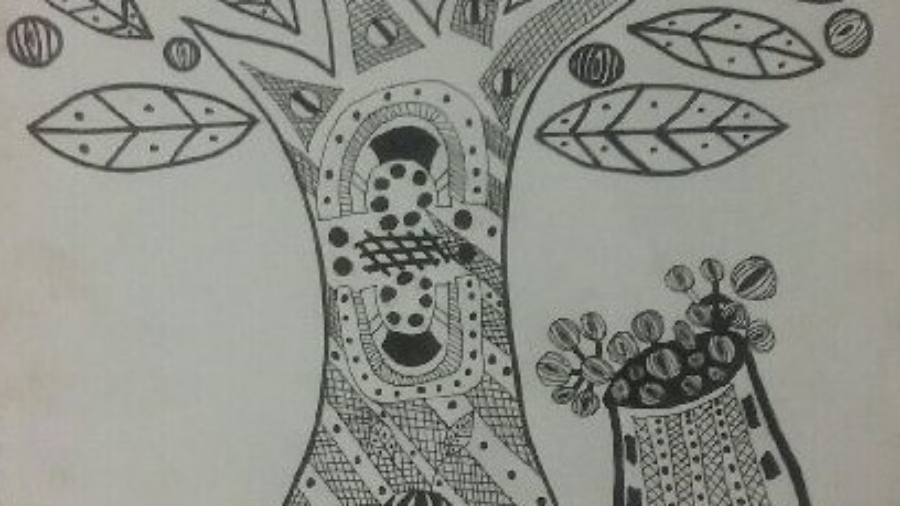

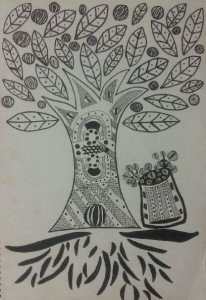

I needed to intervene. So we went back to the drawing board. Literally. My drawing was a massive tree on large pieces of butchers paper taped together. All the parts of the tree were there – roots, trunk, branches, leaves and fruit.

Then as a group we started mapping out what our evaluation looked like. But we didn’t talk about Inputs. We talked about the food and nourishment that a tree needs to grow and the sorts of things that would get our program growing and sustain its life. The nourishment ended up being a long list of good, strong values that would underpin the work.

Words were shared about the project history, much like how it started out like a seed. “The seed represents starting new life and new babies. It is about looking forward to a strong future with our strong families in strong culture.”

When it came to exploring the trunk of the tree, there was strong agreement that this represented culture. Culture wasn’t just in the middle holding up this project strong, straight and proud; it is all around, everywhere. The many practices and traditions which have been around for thousands of years were written on the trunk. There was agreement if the tree was not growing strong, culture has the answers.

As our project had two broad outcomes, these became the two main branches of the tree. It was easy for our group then to consider what it was we would be doing to achieve these outcomes. This became the smaller branches (or the activities of the project) running off the big branches. Attached to this were the leaves, each one representing a stakeholder in the project, helping us collectively to achieve our outcomes. The fruit represented the changes the Review Team wished to bring about for their people and their community. The fruit (aka project impacts) were divided into two sections for each of the big branches.

Although it was not documented on our tree, the metaphor of a storm harming the tree could be used to explore the potential risks to the project. Storms were used in our context to explore the risks to individuals who might be participants in the project, namely the effects of drugs, alcohol and violence. A hope was expressed that “We, the Tiwi people can help ourselves to heal and recover from these storms, just like a tree that regenerates over time.”

Now that our tree drawing was full of delightful fruits bursting with hopes and dreams for their community growing on two strong branches, the evaluator’s attention turned to developing a quality criteria. “How will we know if we are doing a good job in the program?” Of course, there would be a big tunga (a Tiwi woven basket) under the tree overflowing with good quality fruit wouldn’t there? This would tell us the tree (and program) was healthy.

When we started out using the metaphor of the tree to map out what an evaluation would look like for our project, we had no idea how it would go. At one point in our discussion, someone came up with the idea of ‘having a strong sense of direction’ because every seed needs to be planted in the right place, facing the right way. The group agreed “We believe that change is everything, we can all make changes and we can make a difference. Having these beliefs gives us a sense of direction.” The tree was also growing with a purpose; there were particular people we are reaching out for, and this represented our target group.

The Review Team decided that the Evaluation Tree looked like a pinyama (wild bush apple). Ideally, the pinyama tree likes to grow near the beach in swampy conditions but on the Tiwi’s it has adapted to grow in good, sandy soils. It seemed like a fitting tree for this project. It just so happened there was one growing right outside the window where we were meeting. And it was fruiting.

The Review Team became so engaged in this process, they were inspired to harness the skills of an emerging artist to depict their ‘Pinyama Evaluation Framework’ as an artwork (but that is another story). The Review Team has continued in subsequent gatherings to determine how they will test the fruit to see if it is of good quality and good for their people. In other words, how the project impacts will be measured.

Using the tree metaphor to explore and understand the process of Evaluation has allowed this community to see, feel and bring to life their own vision for this project. Of course, it is just a starting point. Like any tree, this vision may change over time as the project grows, changes and eventually bears the first fruit.

In what ways have you used metaphors in Project Evaluation? I’d love to hear your stories.